Who Benefits When Western Museums Return Looted Art?

The repatriation of stolen objects has become a ritual of self-purification through purgation—but who it really serves is less clear than it might seem.

Listen to more stories on audm

The world’s most famous collection of African art arrived in Britain after a spectacular act of colonial violence.

In February 1897, an expeditionary force of 1,200 British soldiers and African auxiliaries crossed the moats and ancient mud walls around the city of Benin, in what is today southern Nigeria. Against defenders armed with swords and muskets, the British-led force deployed machine guns and mobile artillery. Hundreds of Benin residents likely lost their lives.

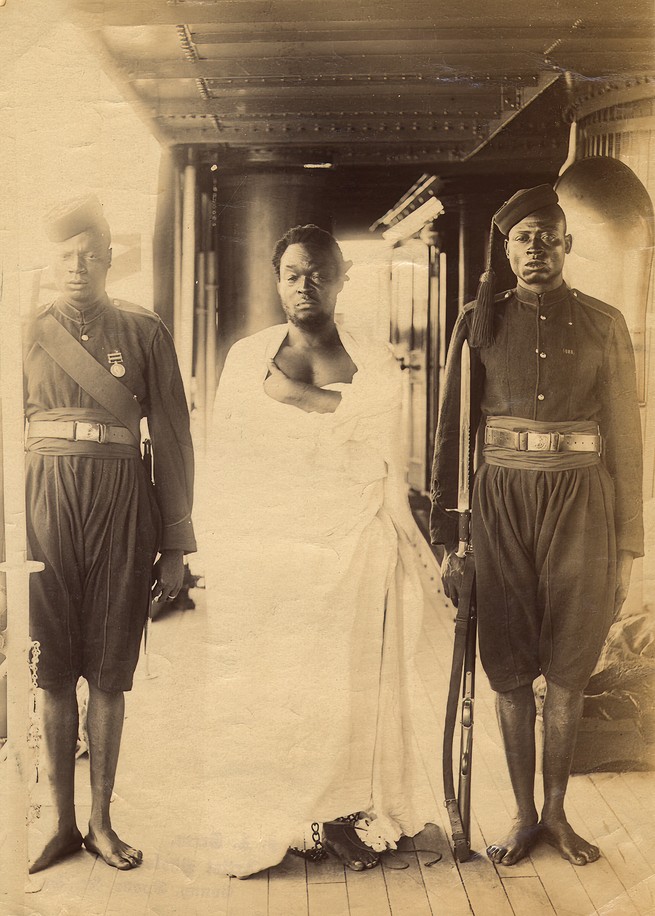

The British drove into exile—and would later capture—Benin’s oba, or king, a man of semi-deified status known to history by his regnal name, Oba Ovonramwen. They looted the royal compound and packed the most beautiful contents into crates to ship home. Then a fire ignited, perhaps accidentally, perhaps not. Shrines, storehouses, the homes and burial places of past obas—all were destroyed.

Most of the spoils were auctioned off in London. The artworks of carved ivory and cast metal were immediately acclaimed as masterpieces: heads of kings and queen mothers, symbolic animal figures, bells to summon the spirits of the ancestors, metal plaques that depicted court life and the great deeds of the obas. The artistry of the finest pieces is extraordinarily delicate. Seen from the side or bottom, a metalwork from the great age of Benin art, from roughly 1450 to 1650, is astonishingly thin, only about an eighth of an inch thick.

A small but telling mistake of nomenclature conveyed the impact of these African works on the European art world. Most of the Benin metal pieces are made of brass, an alloy of copper and zinc. But in London, the pieces were instantly dubbed “the Benin bronzes”—identifying them with the slightly different alloy of copper and tin used in the traditions most admired by the 19th-century British: those of classical Greece and Renaissance Italy. The misnaming stuck as Benin art headed into public and private collections in Britain and around the world.

In British eyes, justice had been served. The 1897 expedition was ostensibly launched in retaliation for the massacre of a British diplomatic mission to Benin earlier that year. Gruesome evidence of a spasm of human sacrifice by Benin’s rulers immediately before the kingdom’s last battle only strengthened the British conviction that their attack had been righteous.

To the people of Benin, however, the sack of their city reverberated as overwhelmingly as if an invading army had captured London, burned Buckingham Palace and Westminster Abbey, and stolen the contents of the National Gallery and the National Archives. The obas of Benin had once ruled an empire that extended from the Niger River westward hundreds of miles toward what is today Lagos. Ancient Benin had no system of writing other than the stories told in cast brass and carved ivory. Art was the kingdom’s culture, its wealth, its literature, its memory. And then the art was pillaged, leaving behind only ashes where palaces and temples had stood for centuries.

The remains of the Benin kingdom were annexed by Britain. (The country now known as the Republic of Benin, situated on Nigeria’s western border, is an unrelated polity.) In 1914, Britain would merge all its Niger River possessions into the colony of Nigeria, an entity that comprised dozens of ethnicities, many alien to one another and some mutually hostile. Even the word Nigeria was a British invention, coined by a journalist named Flora Shaw to describe British holdings in and around the Niger River watershed. (Shaw’s future husband, Frederick Lugard, would become the united colony’s first governor-general, ruling over a territory about the size of Texas and Oklahoma combined.)

At least 3,000 Benin artworks are now owned by public museums or held in private collections around the world, especially in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Nigerians have long demanded the objects’ return. In 2007, a consortium of Western museums joined Nigerians in a “Benin Dialogue Group” to open discussions about repatriation. For more than a decade, the dialogue moved slowly. Then the George Floyd protests of 2020 jolted the group into hyperactivity. The University of Aberdeen, in Scotland, and Jesus College at the University of Cambridge have each surrendered the single Benin piece it had owned. The German government has committed to returning all of its Benin objects; the first two were delivered to Nigerian authorities in July. The Smithsonian Institution has likewise pledged to give most of its small collection of Benin works to a museum in modern-day Benin City. In August, London’s Horniman Museum of anthropology and natural history pledged to return its Benin items. The University of Oxford and its museums may also soon surrender their significant collections.

The campaign for restitution is spreading beyond the Benin treasures. A collection of regalia captured from the Ethiopian empire by the British in 1868 was returned in 2021. Two months later, France returned 26 objects seized from the former West African kingdom of Dahomey. A Munich museum is investigating the origins of dozens of pieces of Cameroon art it holds. All through the museum world, curators face heated questions about what they are holding and why.

To those on the receiving end of this interrogation, the questions can feel deeply ironic. Getting African art accepted into Western art museums was a lifework for many of them. A generation ago, artifacts from Africa were usually displayed in ethnographic museums: the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, not the Louvre; the Museum of Mankind in Mayfair, not the British Museum’s main building, on Great Russell Street; the African museum in suburban Tervuren, not the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in central Brussels.

A great cultural shift occurred in 1982, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, opened its Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, displaying art from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. The British Museum opened its Sainsbury African Galleries in 2001. The Musée de l’Homme’s most important collections migrated to the magnificent new Musée du quai Branly in 2006. Among those engaged in the fight to recognize African art as art were my late parents, Barbara and Murray Frum. They began collecting African art in the early 1970s. Today the highlights of their collection can be viewed in the Art Gallery of Ontario. (Members of my family and I still own some of their pieces. They did not collect Benin art, but the demand for repatriation could ultimately also reach the art they donated to the Canadian public.)

Scarcely had the hopes of my parents’ generation prevailed before the result was challenged by a fierce demand to get the art back out again. Each museum that pledges to surrender some or all of its African collection intensifies the pressure on the holdout institutions to follow. But each of these pledges also intensifies the uncertainty about what exactly is being pledged. What does it mean to return an object “to Nigeria”? What will happen to the objects once they get there?

Where the ancient palaces of the obas of Benin once stood, traffic now whizzes through a large roundabout. Benin City is not a megalopolis like Lagos, but its 1.8 million people still generate a lot of traffic. The most conspicuous structure inside the oval is a huge metal billboard frame. The surrounding fencing is lined by advertisements too. These bright splotches of color distract the eye from other features inside the oval: a derelict monumental fountain; a column that serves as a war memorial; a small, dusty park.

Three buildings give a hint of what used to be here. Two are from the colonial era, with verandas and sloped roofs: the remains of the government compound that the British erected atop the destroyed home of the obas. Nearby stands a rust-red circular structure whose color pays tribute to the mud that coated the exteriors of ancient Benin dwellings. This is the three-story Benin City National Museum, a collection of artwork and memorabilia showing the former grandeur of Benin.

If you turn to the south and then muster your courage to dash across the lanes of traffic that define the oval, you will come face-to-face with a deteriorating hospital: 1970s-vintage concrete, overspread by green tropical mold. But what could sit here one day, relatively soon, has inspired enthusiasm among local leaders and Western curators alike. The crumbling hospital building and its precincts would be replaced by a gleaming museum complex to display Benin art repatriated from the West. David Adjaye, the Ghanaian British architect who designed the National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., has already drawn preliminary plans. A long stretch of ground behind the hospital would be developed as a grand “cultural district”: ambitious new archaeological digs, handsome studios and workshops, world-class schools for artists and artisans.

This new museum, it is hoped, might elevate Benin City into a global destination, much as Frank Gehry’s spectacular museum helped revive the fading industrial city of Bilbao, Spain. New hotels would rise; new businesses would flourish. Underemployed young people would discover productive futures in art, archaeology, tourism, and other services. The traumas of the past would be converted into resources for the future.

The dream of an Edo Museum of West African Art is the brainchild of the dynamic and accomplished governor of the state of which Benin City is the capital. Godwin Obaseki was born in Benin City in 1957. He earned an M.B.A. at Pace University, in New York, then returned to Nigeria to build a firm that grew into one of the country’s leading financial-services companies.

His business acumen led to his appointment as the chair of the economic-development team for Edo State. In that role, Obaseki scored some success against one of Nigeria’s most overwhelming problems: unreliable electricity. Three-quarters of the Nigerian national electrical system has collapsed into dysfunction. On any given day, the national power grid delivers less electricity to approximately 200 million people than the Pepco utility delivers to about 894,000 customers in and around Washington, D.C. Nigerians rely instead on expensive, noisy, and polluting diesel generators that choke the air with scorching fumes.

Obaseki organized the construction of a privately managed gas-turbine facility just outside Benin City. I had the opportunity to visit last fall, and found a clean, efficient, safety-conscious project. From the top of the private-sector power plant, I observed across the road a power plant that was owned and operated by the federal government. That day, as on almost every day, it lay idle, producing not a watt of power. The privately managed facility, by contrast, supplies 8 percent of all the power delivered to the national grid. That achievement and others like it won Obaseki election as governor of the state in 2016, and then reelection in 2020. He hosted the sixth meeting of the Benin Dialogue Group, in Benin City, in 2019.

Obaseki is a tall, elegant man who shifts deftly from the Edo language to formal English or colloquial speech. In his office, I asked him why he attached so much significance to the repatriation of looted art.

“It’s important to understand who you are, how you came to where you are today,” he said. “For us, this project is very important, very significant, because it serves as a reconnection with the past.” And that past really was not so long ago. “Come 1897, there was an invasion. A system, a system we knew then, was brought down … This is an opportunity to try and begin to relate to these works, to reestablish our relationship with them and that connection with the culture and process and tradition that brought them into being.”

To make the Benin museum a reality, Obaseki went to his friend, one of the stars of African finance, Phillip Ihenacho. Ihenacho was born to a Nigerian father and an English mother. He was educated at an elite preparatory school in Nigeria, then at Yale and Harvard. He started his career at McKinsey, the global consulting firm, then earned a fortune by engineering financial deals in the African energy sector. His company helped finance the Benin City power plant that did so much to boost Obaseki’s political career.

For the museum project in Benin City, Ihenacho turned again to the public-private model that had worked so well at the Edo State power plant. He created a private entity, the Legacy Restoration Trust, later renamed the Edo Museum of West African Art Trust. The new trust would assume control over the objects surrendered by foreign museums, then build and operate the proposed museum. Overseen by a board that includes both Nigerian and foreign trustees, the organization is self-financing, seeking support from international donors, not the Nigerian government. The Legacy Restoration Trust proposal almost instantly won international acclaim. Glowing stories appeared in The Times of London, The New York Times, and the house journal of the art world, The Art Newspaper. Many of the stories were illustrated with David Adjaye’s beautiful concept drawings.

The momentum of Ihenacho’s idea seemed almost unstoppable.

Almost.

To the southwest of the traffic circle, less than half a mile away from the hospital, spreads an imposing walled compound. The gates are shut most of the time to most people. On the rare occasions they open, they reveal a white colonnaded mansion set within a large courtyard. This is the residence of the current oba of Benin, who took the name Ewuare II upon his ascension to the throne, but is commonly referred to by his title alone.

The oba captured by the British in 1897 died in exile. In 1914, the British colonial authorities permitted his eldest son to return home, resume the throne, and rebuild a royal seat. Ewuare II is the great-grandson of the oba who restored the monarchy.

I arrived in Benin City on the present-day oba’s 68th birthday, which also happened to be the fifth anniversary of his elevation to the monarchy. I had spent months unsuccessfully negotiating for an audience with the oba, who seldom grants interviews. I’d hoped that once I arrived in town, he and his advisers might change their minds. The radio in the car driving me from the airport buzzed with excited congratulations and birthday wishes. The buzzing only deepened my worry that I might have miscalculated, and that the festivities would bar the oba’s doors to international visitors while I was in town.

The oba of Benin wields little political power. Unlike a European constitutional monarch, his signature is not required to formalize a bill into law. His former kingdom has been folded into a Nigerian republic that now counts 36 states plus a federal capital district, Abuja.

The oba’s economic resources are diminished as well. He is entitled to a stipend from the state government. He receives gifts from supporters and loyalists. He collects earnings from property of his own. With these funds, he is expected to maintain the attendants of his royal court and to support his many dependents, including the households of his five wives.

The royal palace occupies more ground than any private residence in Benin City. But the dwelling itself is overshadowed by the larger and more stylish modern mansions that surround the city’s golf course. In fact, with its short portico, it looks rather like a golf clubhouse itself.

Yet even in his straitened material circumstances, the oba commands tremendous prestige and reverence, verging on awe. One of the most arresting images in the iconography of Benin is that of the “messenger of death”—a frightening head set atop lifelike feet. If a subject of ancient Benin displeased the oba, the spirit represented by the icon was believed to end the life of the transgressor. The night before I traveled to Benin City from Lagos, I had dinner with a Nigerian friend who had grown up near Benin City. Educated abroad, he is now one of the country’s most successful tech entrepreneurs. I asked, “Do people in Benin still believe that the oba can send death?” He laughed uproariously. “Nobody wants to find out!”

And today again, the oba of Benin has a message to send the world: Every last piece of the art removed in 1897 rightfully belongs to him and his family. On May 11, 2021, Nigerian newspapers carried a statement, signed by two high officials of the royal court, that read: “The individuals and persons who parade themselves as … the ‘Legacy Restoration Trust’ … were neither known nor authorised by the Oba of Benin.” The statement affirmed the oba as the only legitimate owner and custodian of royal Benin art. It warned that anyone who contradicted his claim would be considered a “fraudster” and “an enemy working against the interest of the great Benin kingdom.”

People involved in the Benin Dialogue Group would later say this statement came as a shock. But when I did at last get an audience with the oba, he minced no words about the long-boiling grievances that had prompted his denunciation of the governor’s museum plan.

The oba of Benin does not practice the false informality of the modern global upper class. My audience opened with a stately parade of courtiers and attendants. I was required to kneel, clasp my hands, and chant in mangled Edo an incantation of deference and respect. Seated on a gilded throne, with modern Benin metalwork heaped around it, the oba wore white robes and a matching columnar headdress. His body was adorned with the strands of heavy coral beads that symbolize royal power in Benin. He directed my attention to photographs of himself with members of the British royal family.

Like Obaseki and Ihenacho, the oba is a worldly man. He was educated in Britain, then served Nigeria as ambassador to Angola, Sweden, and Italy, among other appointments. I’d clinched my audience with him by emailing his staff an old photo of myself shaking hands with President George W. Bush, autographed by the former president (for whom I’d been a speechwriter). The oba is not such an admirer of the most recent Republican president. Almost the first words out of his mouth were a question to me: “What about this man Trump? Is he still sticking with his Big Lie?”

Protocol forbade me to put questions directly to the oba, so I’d submitted mine in writing in advance. I need not have bothered. Over the ensuing two hours, he spilled out, unprompted, a tale of hurt and betrayal.

The royal family of Benin, the oba said, had joined the Benin Dialogue Group at the very start. It was usually represented by a younger brother of the oba, Prince Aghatise Erediauwa, who is an important Nigerian business figure in his own right. The royal family had imagined a museum to be built on or near the palace grounds, along with some formal recognition of the family’s legal and moral claims to the Benin artworks. The royal family had believed that the entire Nigerian side was united on this point. As late as 2019, the Edo State budget had allocated a sum of 500 million naira (about $1.2 million) to help build a new “royal museum” of Benin art.

Then came a startling new proposal: the replacement of the royal-museum project with a museum controlled by an independent board headed by Ihenacho.

According to the oba, the first he heard of the concept was from a terse letter dated March 21, 2021. The letter requested that the oba authorize the trust to undertake all negotiations about the artworks, to act as the custodian of any artworks returned to Nigeria, and then to hold and display the artworks in its own museum. The letter was signed by Ihenacho. It provided a small blank space for the expected countersignature by a representative of the royal palace.

The oba found every line of the letter insulting, beginning with the salutation, “Your Excellency”—a breach of etiquette so offensive to the court that on the copy provided to me, somebody had actually scratched it out and substituted, in handwriting, the preferred “Your Royal Majesty.”

The oba insisted to me that this request had come out of nowhere. He had never even met Ihenacho. But it was not Ihenacho at whom the oba directed his fiercest ire. It was Obaseki.

“We had our dear governor”—the oba pronounced the phrase with heavy irony—“saying, ‘We are collaborating with the palace. We are collaborating with the palace.’ But I didn’t see this collaboration!”

The oba accused the governor’s camp of plotting to sideline him. He lingered on a particular humiliation: the vision of a future in which visitors would come to Benin to view the treasures of his royal ancestors in a museum owned by a private company, designed by an architect not of the oba’s choosing, on state land rather than royal ground.

Courtiers showed me the plans for the museum they want—an edifice blending more and less classical elements, similar in style to the oba’s own residence. Decorum prevented me from saying it aloud, but I liked the David Adjaye sketch much better. Yet was that not exactly the problem? The contrast between the global cool of the Adjaye sketch and the much more flamboyant design unrolled before me in the throne room almost too neatly illustrated the central question of the Benin restitution debate: Whom exactly is this project for?

A long and tense history divides the families of the governor and the oba. In the mid-1890s, Obaseki’s great-grandfather served then-Oba Ovonramwen as keeper of the royal accounts. According to Obaseki, as British emissaries traveled from the coast toward Benin, his great-grandfather urged negotiation and conciliation. He had traded with the British, and he knew their power. His advice was disregarded. Then followed the ambush and the catastrophic retaliation. The victorious British executed the Benin nobles whom they blamed for the conflict—and installed Obaseki’s great-grandfather as acting ruler of the Benin kingdom.

The Obaseki family benefited from the educational and economic opportunities that the invaders offered. Family members mastered the invaders’ language. They learned to play by the invaders’ rules. They grew rich and influential—but they paid for this success with the enduring distrust and dislike of the Benin royal family.

Both Obaseki and the oba are patriots of Benin. Both crave the honor of regaining Benin’s artistic treasures and renewing Benin’s urban grandeur. The governor’s plans anticipate, as his great-grandfather warned in 1897, that Benin’s goals are most likely to be achieved by accepting Western terms. The oba insists, like his great-great-grandfather, that Benin will meet the world on its own terms, without concessions to outside pressure.

Who will win? Nigeria is an intensely religious country. In Edo State, the dominant religion is Christianity. To get a sense of local public opinion, I visited several prominent Pentecostal elders and evangelical pastors. As Christians, all of them were ambivalent about the idolatrous aspects of traditional Benin art. But when pressed about the outcome of a power struggle between the oba and the governor, they were emphatic and unanimous: The oba would prevail.

Whoever ends up as the decision maker over repatriated Benin artworks and the accompanying grants from Western governments and foundations will control hundreds of jobs and tens of millions of dollars in building and operating contracts. The ability to award jobs and dispense contracts translates into enormous political power—and oftentimes into personal wealth for the hirer and contract-dispenser. Edo State’s budget was only about $500 million this year. An entity or person spending tens of millions of dollars to construct a museum—and many millions to operate it—would instantly become an overwhelmingly important player within the former kingdom of Benin. That’s a prize worth fighting for. However, as the governor and the oba circle each other, another contender lurks, the most powerful of them all: the Nigerian national government.

The Obaseki-Ihenacho concept of an independent, private museum was not devised to spite the oba. It was developed, fairly obviously, to protect returned Benin art from a national government that has miserably—and often maliciously—failed to protect Nigeria’s cultural heritage. The dismal record is well described by Oluseun Onigbinde, the head of a fiscal-transparency group called BudgIT. Onigbinde is the author of a 2021 book, The Existential Questions, an unblinking analysis of contemporary Nigeria’s most urgent problems. He, too, hopes to see the Benin pieces returned someday, he told me recently. Here and now, however, “the management is very, very poor at our museums. A lot of times, people find themselves in those places not because they are qualified, but by chance. You have a lot of people working in those places who do not understand the mission, especially at the leadership level. There are no strong rules around the management of museums: who gets access to the art, who is accountable for it. I went to the museum in Kano. It was really poor, how pieces were kept. Someone could break in and walk away with anything.”

This is not the first time an effort has been organized to return art from Nigeria to Nigerian control. Years before the reckoning of 2020—years before this article’s principal characters were even born—a British colonial official named Kenneth Murray set out to endow Nigeria with a museum worthy of its heritage. The eventual degradation of Murray’s legacy by corrupt officialdom haunts every discussion of Nigerian cultural property. The story is well told in Barnaby Phillips’s Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes, published last year.

Murray arrived in Nigeria in 1927 to teach art. He became fascinated with Nigeria’s artistic heritage. For decades, local people in the central Nigerian hill country had unearthed clay heads and figures of unusual fineness and beauty. In 1943, the colonial government subjected some of these pieces to scientific testing. They dated back 2,000 years or more. The discovery inspired the colonial authorities to create a Nigerian Antiquities Service, and to appoint Murray as its first director.

At the end of the Second World War, Murray approached his superiors with an idea. In the decades after 1897, German museums had acquired hundreds of Benin artworks. Now Germany was defeated and bankrupt, while Nigeria was flush with earnings from its wartime exports to Britain. What if Nigeria used some of its windfall funds to buy its own art back from Allied-occupied Germany? The occupation authorities eventually vetoed that idea. But in the meantime, Murray had secured a substantial budget. He bought pieces from British private sellers. And then a bigger opportunity opened up.

Murray’s top aide in Nigeria, Bernard Fagg, had a brother, William, who worked in the ethnography department of the British Museum. William Fagg, too, was seized by the vision of a great museum for Nigeria. He used his power at the British Museum to sell pieces out of its collections to Murray’s Nigerian Antiquities Service.

In 1951, Murray acquired two Benin plaques for Nigeria from the British Museum in return for some objects from the Nigerian Antiquities Service and 25 pounds, a shockingly low price even then. William Fagg bought other important pieces at auction in London on Murray’s behalf. Murray leaned on British companies that did business in Nigeria to donate money to fund his purchases. Fagg ensured that the deeper-pocketed British Museum did not bid against Murray.

In 1957, a new Nigerian National Museum opened its doors in the then-capital, Lagos. It possessed 90 Benin pieces. Fifty-five of them had formerly belonged to the British Museum. When Nigeria gained its independence, in 1960, Lagos held a collection of Benin art exceeded only by those in London and Berlin, plus many more treasures from Nigeria’s numerous other artistic traditions.

I visited the Nigerian National Museum twice during my visit. Built in a low-slung style around a courtyard, the building has gradually crumbled upon itself. Between the museum building and the parking lot, a scruffy expanse of what might once have been a garden is speckled with litter. Inside, long-defunct wires dangle untrimmed from stained and broken ceiling tiles. The huffing-puffing sound and diesel smell of the museum’s weak electrical generator penetrate everywhere. Where the sun does not reach, the museum is cast in gloom, owing to its many burned-out light fixtures.

The National Museum does not entirely lack resources. It employs about 200 people, from the museum director through the curators to the attendants, the security guards, and the woman sleeping head-down on the counter of the tiny gift shop. During my first tour of the museum, at midday on a Monday, I saw no other visitors—this in a metropolitan area of more than 20 million people. There were none on my second either, at midday on the following Sunday.

During my first visit, I was being led by a curator toward the Benin section when all the lights cut out. The day’s diesel-fuel allocation had been exhausted. I viewed a few Benin pieces by the light of my cellphone. I would have to return, I was told, to see the most iconic of the items acquired by Murray and the Fagg brothers.

The number of Benin pieces on display in the National Museum falls far short of the number acquired by Murray and the Faggs. It is of course not uncommon for a museum to display only a portion of its holdings. But important pieces have disappeared from the Lagos museum over a period of many years.

In June 1980, Nigerian diplomats bought four Benin pieces at auction in London for ₤532,000. Soon after the pieces arrived in Lagos, the ceiling of the museum’s storeroom was breached and the new pieces were stolen. Barnaby Phillips’s reporting proved that two Benin plaques acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1991 had been stolen from the Murray-era collection in the National Museum. (The Met has since returned them.) Phillips traced another of the Murray-era pieces to a private collection in Europe.

When thefts have been detected, Nigerian authorities have typically blamed low-level museum employees. But in 1976, the head of the ethnography section at the British Museum warned the British government that Nigerian politicians were “plundering their own collections.” At times, the plundering was not even surreptitious. In 1973, Nigeria’s head of state at the time, General Yakubu Gowon, paid an official visit to the United Kingdom. He wanted to thank the British for their support of the federal side during the Nigerian civil war of 1967–70, a bloody conflict in which as many as 2 million people died. So before he departed Nigeria, Gowon walked into the Lagos museum and selected one of the Benin heads collected by Murray and the Fagg brothers, which he then presented to Queen Elizabeth. The British apparently at first assumed that the head was a reproduction. It remains in the Windsor collection to this day, posing political quandaries that embarrass both the British and the Nigerian governments.

Governor Obaseki’s museum concept and its independent board were designed to prevent the recurrence of these bad practices. That is the hope, at least. But how realistic is it?

One of the very first people I met in Nigeria was the minister of information and culture, Lai Mohammed. We spoke in the lobby of a hotel near his Lagos home. Mohammed is a lawyer, businessman, and deft political operator. When we spoke, in October 2021, his ministry was enforcing a ban on Twitter in Nigeria—punishment for Twitter’s brief suspension of Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s account. Buhari had threatened violence against opponents. His threats should not be dismissed as bluster. As a general in the army, he had seized the presidency in a 1983 coup. He governed repressively before he was toppled by a countercoup in 1985. Popular disenchantment with civilian rule enabled Buhari to regain power by election in 2015 and to win reelection in 2019. Now 79, Buhari remains a vigorous and even menacing presence.

Mohammed pronounced to me an emphatic statement of federal supremacy over all other claimants to the heritage of the Benin kingdom. “There is no doubt, no contest, about the exclusive authority of the federal government to the exclusion of either state or traditional authorities in matters relating to monuments, museums, and artifacts,” he said.

Since Nigeria gained independence, political power has been closely held at the federal center—and that center has intentions of its own about the Benin artworks. The artworks thus far returned have been claimed by the federal authorities. Buhari has presented some of the first repatriated artworks to the oba as a matter of executive discretion. Assuming Buhari leaves office on schedule, in May 2023, the next president will wield discretion of his or her own. Antiquities collectively worth many hundreds of millions of dollars could soon exit Western museums without any agreed-on plan for how those antiquities will be displayed or how they will be protected from the sad fate of Nigeria’s other government-managed cultural institutions.

The corruption of the Nigerian state is an unavoidable fact. The country ranks 154th out of 180 countries included on Transparency International’s index of public-sector corruption, as perceived by experts and businesspeople. Its federal government is almost purely predatory, providing little physical security and few public services to its people. Nigeria is a society of incredible dynamism and innovation. Drive through central Lagos, and you see the buildings where Google, Microsoft, and Oracle employ the talent they recruit there. The whole world dances to music by Nigerian artists like Burna Boy. The country is also home to a successful movie industry, locally nicknamed “Nollywood.” On my visit to Benin City, I watched the filming of a scene for a historical drama set on the eve of the British invasion. All of these creative energies must operate around and against an indifferent and parasitic national government.

Much of Nigeria’s oil wealth is stolen by political and bureaucratic elites, then removed from the country altogether—stashed in Dubai banks or London real estate. What remains is shared within patronage networks that exist to maintain the rulers’ power. The predation at the top is emulated by lower-ranking officials: police who demand bribes, customs officials who demand rake-offs from imports. Nigerian political elites claim to speak in the name of their people, but too often show scant regard for their people’s well-being.

It’s possible to imagine a corrupt state sustaining a prestigious cultural institution in the same self-advertising way it might build a flashy new airport. Mexico, which is ranked No. 124 on the Transparency International index, hosts a magnificent anthropological museum and takes reasonably good care of cultural sites. But many of those who have controlled the Nigerian state have looked at any assets and seen only valuables that will be seized sooner or later by somebody. So why not now, and by you, if you have the opportunity and the means?

When I raised the Nigerian government’s past record with Lai Mohammed, the culture minister, he retorted, “You can’t steal my property and then when I ask you to return it, you answer that you don’t have confidence how I’m going to keep it.”

This line of reasoning resonates powerfully in the West, supported by the work of radical critics of Western museums such as Dan Hicks. Hicks is a curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum, at the University of Oxford, and a fierce advocate for the return of Benin works. In 2020 he set forth his views in a passionate polemic, The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution:

The arrival of loot into the hands of western curators, its continued display in our museums and its hiding-away in private collections, is … an enduring brutality that is refreshed every day that an anthropology museum like the Pitt Rivers opens its doors.

Hicks urges the immediate return of artworks taken by European colonial powers to their places of origin. Western people, he believes, have no business worrying about what happens to the art after that. Instead, their focus should be inward, upon themselves and the iniquities of their own culture. “It’s time to start to bring this episode to a conclusion, by understanding, rejecting and dismantling this white infrastructure,” he wrote.

Yet the consequences of viewing restitution as a ritual of guilt and atonement, of self-purification through self-purgation, cannot be waved away. Western museums are extremely reluctant to express their doubts about the uncertain fate of pieces returned to Nigeria. The curators I interviewed all spoke only on deep background. At one major Western museum, the curator I interviewed was accompanied by a professional minder who recorded every cautious word uttered.

In a Lagos art gallery, I met by chance one of Nigeria’s preeminent collectors, Olufemi “Femi” Akinsanya. Only a few hours earlier, I’d been looking at a book whose cover was graced by a piece from his collection. Nigeria is home to a lively art market, much of it contemporary. Akinsanya collects modern art too, but the core of his collection consists of older works from Nigeria’s many different cultural traditions. He invited me to his townhouse in one of Lagos’s richest neighborhoods for a tour of his collection, which he’d begun to accumulate years before. I asked his views of the three-way tussle among the oba, Obaseki’s group, and the federal government.

“We don’t have a very good tradition with government institutions in culture,” he told me. “African art always belonged to individuals, groups, and families. The claim of ‘Nigeria’ to the art is kind of dodgy. The record of government with museums, I am sorry to say, is disappointing.”

Akinsanya believes that the Benin bronzes “should go to an institution not directly controlled by the government,” and that “there ought to be a binding commitment that every returned object is recorded in a register. We have to make it difficult for objects to disappear.” Phillip Ihenacho, in our last of several Zoom conversations, said that such a registry would be a priority for his trust. But he also wearily acknowledged that he could not guarantee that no returned piece would be stolen.

Art security aside, there would be a certain irony to the federal government of Nigeria becoming the custodian of the Benin bronzes. The British colonial authorities favored the Hausa and Fulani peoples of the north for their military recruitment. Since independence, the north has tended to dominate the Nigerian state. That domination triggered the Nigerian civil war of the 1960s, when the Igbo people of the south tried to form their own independent state, Biafra. The area around Benin City attempted to stay neutral in the war. Instead, it was first invaded from the south, then occupied by the north. The federal forces eventually starved Biafra into submission. In some ways, the present Nigerian federal state has continued rather than replaced the system that overthrew the kingdom of Benin in 1897.

In 1991, the capital of Nigeria was moved from Lagos to Abuja, a planned city almost 500 miles by road to the northeast, on the dividing line, more or less, between Nigeria’s Christian south and Muslim north. Abuja is the seat of Nigeria’s presidency, its National Assembly, and the offices of state governments seeking grants and favors from the central authorities. What the city lacks is national cultural institutions. It is Washington, D.C., without the Smithsonian museums or the National Gallery of Art. In January, Abba Tijani, the director general of the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments, gave a speech that proposed the development of a major museum in the capital as one logical destination for repatriated Benin artworks. What exactly would be accomplished by relocating the art of Benin from the former imperial capital in London to an only somewhat less remote imperial capital in Abuja?

But who, then, should be the ultimate steward of the Benin bronzes?

The plundering of Africa’s artistic heritage inflicted a double injury upon the people of Africa. First, and most obviously, Africans were severed from their history and culture. Their greatest treasures were expatriated from their places of origin to the public and private collections of foreign conquerors. Second, the relocation memorializes Africa’s history of subordination. When Nigerians must travel to London or New York to see the masterworks of their homeland, they are symbolically reminded that this history of subordination has not ended yet. The injury hurts all the more because it is so difficult to institute an effective means of redress.

Dreams of Benin City as the next great cultural destination bump into the tough practical difficulties of travel to and within Nigeria: slow and expensive tourist visas, unsafe roads, unreliable air connections, and physical danger to travelers, including a significant kidnapping industry. What’s more, Governor Obaseki is term-limited. He will be out of office by the end of 2024. Nigerian states have troubled records of starting ambitious projects under one governor, only to abandon them under the next. Rivers State, in the Niger Delta, commenced building a new monorail system in 2010 for its capital. The state spent $400 million on the prestige project. Then the governorship changed hands, and the project was abandoned unfinished.

The claims of the oba, meanwhile, are shaped by the legal reality that he’s not the head of any government. Returning the objects to him means converting what was once the sacred property of a reigning king into the personal wealth of a single family. In precolonial Benin, the oba was the only permitted commissioner of cast-metal art. The oba might present metalworks as gifts to supporters, but before 1897, Benin art was not a marketed good. Today’s Nigeria is governed by British-style property laws. If a contemporary Nigerian owns a piece of art, he or she can of course sell it. And while the present oba has vowed to preserve in a future museum any art objects returned to him, he has heirs, and they will have heirs. There will be expenses and business reversals and divorces in the decades ahead—and now a new portfolio of family assets to cover any shortfall.

There are more fundamental questions to be pondered here, questions about whether history can be—or should be—unwound. Projecting the identities of the present upon the art of the past almost inevitably yields illusions, or worse. Consider another famous expatriated treasure, the Pergamon Altar, now in Berlin. It was commissioned by a Hellenistic Greek-speaking king for his capital near the western coast of what is now Turkey. Should the altar be restored to Greece? To Turkey? Museum collections are human institutions. They can and should be scrutinized and criticized. But the standards of scrutiny must likewise be scrutinized. A standard that art should belong to the present-day government of the place where that art was created centuries ago is not, to me, sustainable.

Nor can present-day owners of art erase the brutalities of the past by casting the art away. The human past was a grim place for almost everybody, and few of those with the resources to command art in the first place were free of culpability for something dreadful—very much including the rulers of Benin.

The kingdom of Benin rose to greatness at almost exactly the same time as the Portuguese carved the nearby island of São Tomé into sugar plantations. In the early 1500s, São Tomé was the largest sugar producer in the world, and Benin provided many of the human bodies that did the work.

Ancient Benin produced cloth, pepper, and ivory—but not its own metal. The obas of Benin obtained the material for their glorious artworks by trading people they’d enslaved for brass sold by Portuguese merchants.

Changing patterns of commerce relocated the sugar industry from São Tomé to Brazil by the early 17th century. The slave trade shifted westward along the African coast. The Benin kingdom and its art went into decline soon afterward. Like the Roman Pantheon and Thomas Jefferson’s mansion at Monticello, the art of Benin flaunts the wealth gained by slavers. That history does not detract from the objects’ beauty. But it cannot be detached from the objects’ meaning.

Almost everybody I spoke with in Nigeria expressed a wish that the Benin pieces be returned to one or another of the competing claimants. The wish was expressed even by people with otherwise scant interest in art. European colonialism brought Africa into the modern world, but always on someone else’s terms. Colonialism left behind road networks built to serve international markets, not local commerce; armies and police forces in which orders are issued in the former colonizer’s language; governments that to this day regard their people as subjects to be exploited, not citizens to serve. The removal of so much of Africa’s material heritage to foreign capitals may not be the most urgent or important of the negative legacies of colonialism. As Oluseun Onigbinde cautions, only a small, elite minority in Nigeria would list the repatriation of art among the country’s top-10 problems. But for that minority, the removal of heritage objects is among the most visible and emotional traumas of colonialism. What we are talking about when we talk about the expatriated art of Africa is much, much more than the art itself. “Art is a powerful way to see what binds us together: This is what I came out of, ” Femi Akinsanya told me. “And it’s a way of reckoning with that heritage, in all its complexity.”

It’s a compelling thought. But it raises another question: In the realm of art, which human beings count as “us”? In 1907, a 25-year-old Pablo Picasso saw African masks in the dust of Paris’s very first anthropological museum, then housed across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower. The encounter launched Picasso into a new phase of his own art, by teaching him that painting “is not an aesthetic process; it’s a form of magic that interposes itself between us and the hostile universe, a means of seizing power by imposing a form on our terrors as well as on our desires.” A few weeks later, Picasso completed work on his famous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, in which African masks substitute for the faces of two of the five nude female figures. In Picasso’s vision, Africa had become a fountainhead of the art of the modern world.

An infrastructure of art curatorship is rising in West Africa. The Chinese government has donated millions of dollars to help build an impressive new museum in Senegal to house works that the French government has loaned. Across the road from the dilapidated National Museum in Lagos stands a center dedicated to the culture of the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria. The Rele Gallery, in Lagos and Los Angeles, offers for sale new works of pulsing vitality. It’s all there to be admired and celebrated.

But along with that celebration of the emerging, I suggest a defense of the existing. The Western museum is a great accomplishment of human civilization. Museums may trace their origins to the crimes of kings and the arrogance of colonizers. In the here and now, they allow tens of millions of people to enjoy what were once the personal pleasures of a wealthy, powerful, titled few. Museums within stable states offer unmatched security for fragile and valuable treasures. Museums at centers of international commerce and travel connect rare artifacts to mass audiences. Before the coronavirus pandemic, the British Museum drew nearly 4 million visitors a year from outside the United Kingdom. Three-quarters of the Louvre’s nearly 10 million annual pre-COVID visitors came from countries other than France. The large and growing African diaspora in North America, too, should be able to see its heritage in museums in New York, Chicago, Washington, and Toronto.

There is more great art in this world than there are places to properly display it. I toured the Benin collection in the British Museum with Barnaby Phillips, the author of Loot, a few hours before my flight to Lagos. “How many Benin pieces do you see here?” he asked. I counted some 65. He replied that in 1897, the British hauled away at least 3,000 ivory and metal objects. How many objects would a new West African museum of Benin art wish to display? Thirty? Forty? A hundred? “Surely,” Phillips said, “there’s enough to go around?”

Other accommodations could be imagined as well, including museum collaborations and financial compensation. International exchange programs could bring warehoused art from Berlin and London to traveling temporary exhibitions across Nigeria. Those could be joined to new projects to expand opportunities for careers in the arts and culture—fields where, right now, Nigerians find their best opportunities by emigrating. Scholarships for promising artists and artisans could be expanded, and the contemporary art of Africa brought more urgently to the attention of world markets. I had the pleasure of visiting the museum founded by Prince Yemisi Adedoyin Shyllon at Pan-Atlantic University, east of Lagos. Unlike the government museum downtown, here everything was meticulously curated by a small and efficient staff. I discovered artists previously unknown to me whose work I now follow closely.

Displays in Western museums could be revised to provide better insight into the culture that created the art. In the British Museum, for example, there’s the Benin art and there’s text on the wall about the expedition of 1897. Why not a modeled reconstruction of the palace compound, to draw attention to the civilization that created the art before 1897? Benin City itself is crying out for archaeological investigation, and for the restoration of the historic city’s ambitious network of walls and moats, now sadly tumbled and garbage-strewn. Archaeological work was envisioned in Governor Obaseki’s concept for an independent museum of Benin art. But even if that concept falters, outside support can help the digs proceed. Perhaps a replica of some of the old royal quarters could be built, much as the city palace of the Prussian kings has been reconstructed on its former site in Berlin. The claims of the royal family of Benin could be answered with financial restitution, perhaps in the form of a foundation under their patronage to support the arts and culture of Edo State.

New technology offers even wider possibilities. A consortium of German museums is launching a website, Digital Benin, that will make the artworks of Benin—and scholarship about those artworks—instantly accessible to anyone with an internet connection. As virtual-reality technology comes to market, that art could become viewable in three dimensions and at full scale. Perhaps the day will come when we can put on goggles and gloves and go for a walk through the royal palaces of Benin at the zenith of their glory.

There is a crucial need for expansive, optimistic thinking to replace the polemical rancor that often distorts discussion today. Some of this work has already begun. More should follow.

Too many people look to art objects to do things that art cannot do: redress grievances, salve shame, absolve guilt.

We should be able to honor the past; empower the descendants of those from whom the art was taken; protect the art itself from theft and decomposition; and ensure that the art can be seen as widely as possible. It took enormous effort to overcome the supremacist view that African art was inferior to European art, or that it was not art at all. Now the whole world celebrates the cultural achievements of Africa and the artistic genius of Benin.

That celebration should only grow larger. The artistic works of all humanity are the common heritage of all humanity: all of those works, and all of us.

This article appears in the October 2022 print edition with the headline “Who Do the Benin Bronzes Belong To?” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.