Most of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work is in storage.

Nearly half of Pablo Picasso’s oil paintings are put away.

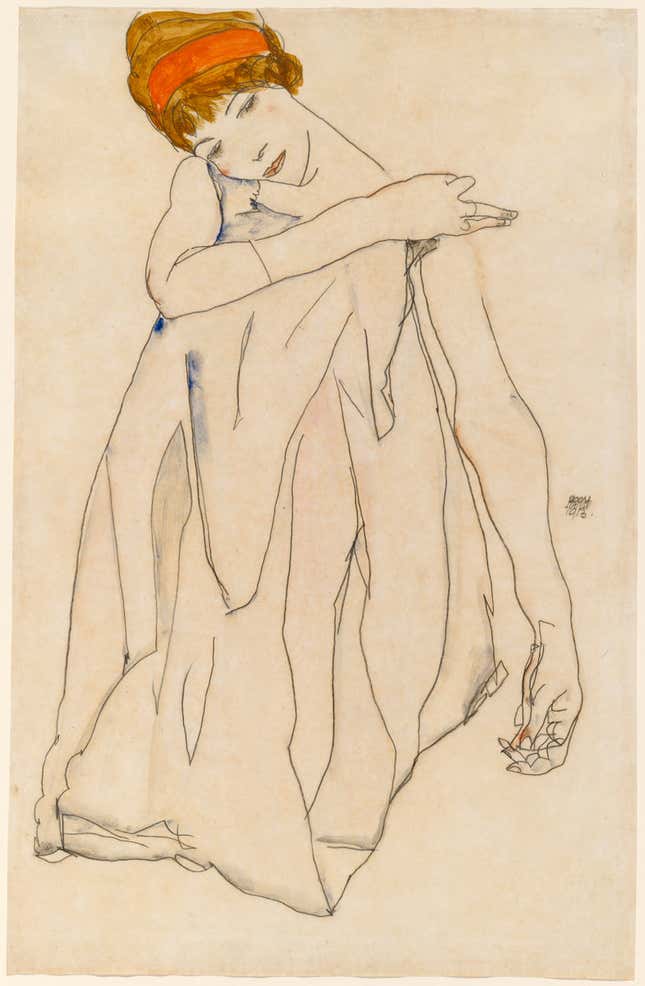

Not a single Egon Schiele drawing is on display.

Since the advent of public galleries in the 17th century, museums have amassed huge collections of art for society’s benefit. But just a tiny fraction of that art is actually open for people to view and enjoy—including, it turns out, many works that are considered masterpieces. The dynamic raises questions about who actually benefits when museums collect so much of the world’s best art.

To paint a picture of these curatorial decisions, Quartz surveyed the holdings of 20 museums in 7 countries, focusing on the work of 13 major artists. In total, we collected data for 2,087 pieces of art. The statistics above are drawn from our survey, and here are the key results:

Counting masterpieces

Much of the world’s great art is housed in the vast archives of museums with limited display space. The largest museums typically display about 5% of their collection at any time. Wealthy patrons who donate art to these museums often end up hiding it from public view.

Museums don’t usually report what portion of an artist’s work they have on display. The institutions we asked for that information either refused to provide it or didn’t respond to our requests. So we collected the data ourselves using the museums’ own websites, many of which now display all of their art. (Some, like New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and London’s Tate made our job easier by also publishing the raw data.)

We surveyed a wide range of museums, including some of the world’s largest, like New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art (NGA), and Saint Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum. (Here is the full list of surveyed museums, including many that couldn’t be included in our analysis.)

Lacking complete data, we chose instead to search the collections for individual artists of particular renown. Results were limited to a single medium for each artist, typically their most recognizable: O’Keeffe’s oil paintings or Alexander Calder’s sculptures, for instance. Online collections are often incomplete, so the results of this survey shouldn’t be considered comprehensive, but there is enough to data to get a sense of how often work by major artists is kept out of view from the public.

Quartz’s survey found that the rate at which famous artists are displayed varies widely. Paintings by Paul Cézanne and Claude Monet were the least likely to be hidden away. Other artists received much less generous treatment, notably Schiele, an Austrian whose depictions of the human form were influential on the Expressionist movement. He did not have a single work on display despite 7 different museums holding a total of 53 of his figurative renderings.

Display rates for each museum also vary, though these numbers can be somewhat misleading. The display rate at the NGA, for instance, is skewed by 199 Rothko paintings held in storage. (They have two on display.) This represents a sizable portion of the artist’s life work, which was donated by the Rothko Foundation in 1986. According to chief curator Frank Kelly, at least a dozen of those paintings will be on display when the museum’s East Building reopens after renovations.

Into the vault

Artists, collectors, and foundations donated the vast majority of the art represented in this survey. In addition to the potential tax write-off, benefactors often view large museums as the only places that can guarantee important works of art will be properly conserved. They may also seek out institutions that have a policy of never selling the work, as the Rothko Foundation did with the NGA.

As a result, art tends to accumulate in the storage vaults of big museums rather than the galleries of smaller ones. Moreover, the roughly 5% of their collections that museums do display is usually rotated among the most culturally important works they have. Less significant or niche works may never leave the archives except to be conserved. A 2002 dissertation found that at the Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, which are included in our survey, donated items were displayed much less frequently than purchased ones. (pdf, p. 121).

Thirteen of the museums we surveyed collectively hold 862 photographs by legendary street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. Almost all of them were donations. Many of those in MoMA’s collection were gifted by the author himself. Only one is on display, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), even though Cartier-Bresson has been the subject of a major retrospective as recently as 2010.

We chose to exclude works by Cartier-Bresson from the rest of our analysis because there are so many of them, skewing the results. But here’s a look at just how much of his photography is in storage:

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with a museum having art that it does not display. Much of the art in storage is part of “study collections” that museums never had any intention of displaying. These items are often of less public interest than those in the “display collections,” but can still have tremendous value for research. Nancy Thomas, who manages the collections of LACMA, pointed to a collection of Luristan bronzes as an example of items that are more valuable as a group, even if they can’t all be displayed. “It’s multiple dissertations waiting to be written,” she explained.

Other works may be intended for display, but require frequent preservation in order to ensure their survival. Cartier-Bresson photographs and Schiele drawings are works on paper, which will fade if exposed to light. Textiles and other objects may have similar issues that prevent them from being on permanent display.

However, the the vast majority of the works included in this survey are not study collection pieces, nor are they particularly fragile. Most are paintings by recognized masters who draw great public attention. Taken together, only 44% of the art included in the survey was on display. That’s 689 works in storage for just the dozen artists we surveyed. That so many celebrated works are out-of-sight raises issues that go beyond day-to-day operation. They force a larger question: What are museums for, anyway, and whom are they supposed to benefit?

There is surprisingly little agreement about the purpose of museums. Some, particularly the older ones, tend to see conservation and research as top priorities. NGA Curator Frank Kelly described their archive as a key part of the museum. “Our whole mission is to protect works of art and that includes storing them properly,” he said. Archiving hundreds of paintings by a single artist makes good sense if your goal is to protect the art indefinitely. Kelly also stressed that this allows them to loan works out for display in other museums.

Smaller and newer museums are pushing the other way—toward more explicit focus on the public. Cost is one reason. Collecting art is more expensive than it’s ever been. Once a work is purchased, the cost of storing it can be prohibitive. LACMA curator Nancy Thomas described storage to Quartz as “an issue for all museums.” She explained that sculptures and installations are especially problematic as they must be individually palletized. A 2013 survey of Canadian museums found that storage size and conservation costs were their primary concerns (pdf).

Sales, sharing and the web

The most obvious solution to these problems would be for museums to sell works that they aren’t displaying. In the museum world, the controversial practice of removing art from collections is euphemistically referred to as deaccessioning. Many smaller museums, not to mention private collectors, would love to accession one of the 30 stored Picasso paintings held in storage by MoMA. In theory, museums could simultaneously solve their financial problems and also end up with more art on display.

However, the policy argument is often irrelevant because most museums are not allowed to sell or give away the art. Many museum trade associations effectively ban sales. The Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) allows for art to be sold (pdf) under certain circumstances, but the funds raised must be used for the purchase of more art. The AAMD has explicitly blacklisted museums that have sold art to try to escape from financial struggles.

Michael O’Hare, who teaches public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, challenged these policies last year by arguing museums should value their art as an asset. In his estimation, selling 1% of the value of Art Institute of Chicago’s collection could endow free admission forever and pay for improvements to educational programs and other public-facing endeavors.

Asked what the response from museum curators had been to his article, O’Hare said, “Silence.”

It’s not surprising that museum curators are resistant to economic arguments about their art. But curators, particularly in the United States, rarely even acknowledge that large collections of unseen art could ever pose a problem. There is a great deal of institutional discussion about how to manage such collections, but much less about whether they are a good idea. One exception to this rule is a 2010 article by Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) curator Ann Temkin in which she muses on the dangers of ever-growing collections (paywall), even worrying that museum storage “will start to resemble cemeteries nobody visits any longer.” Temkin implores her fellow curators to tackle the issue of storage head-on. (She was unavailable to be interviewed for this story.)

Museum curators in the United Kingdom seem more willing to address the questions posed by storage: The latest issue of their trade magazine is devoted to the topic (paywall). Suzanne Keene, a retired professor and the author of a 2008 report on the use of collections in the UK, said in an interview that attitudes toward collections are often driven by the curator’s personality. “So much comes down to individual people, basically,” she said.

Philosophical resistance aside, many curators are pursuing ideas for better utilizing their stored collections. Some institutions, such as the Brooklyn Museum, are investing in “open storage” solutions that still allow the public to browse the art, such as glass cases and sliding racks. The recently opened Broad Museum in Los Angeles goes one step further and offers windows onto the vault where museum staff are actively working. Whether such approaches could ever put more than a small fraction of stored collections on display is an open question.

A new way of thinking

Others believe museums simply need to change the way they think about collecting. A Smithsonian policy analysis from 2005 suggested several “alternatives to traditional collecting” (pdf) that could decrease the size of stored collections, or at least prevent them from growing at an unsustainable rate:

- coordinating collection efforts of multiple museums to reduce overlap

- renting art from other museums

- joint purchases by multiple institutions

- sharing collections through long-term loans

- collecting images or models rather than original works of art

One suggestion they don’t mention—keep in mind this was written in 2005—is the very thing thing that allowed for this story to be written: publishing collections online. This, in fact, seems to be the approach most museums have adopted. Their enthusiasm to digitize the art at least ensures that many of these works can be seen by someone determined to seek them out. Virtually all of the 48 museums Quartz looked at had at least some of their collection online.

Clicking around a website remains a poor substitute for the experience of wandering a museum and suddenly being confronted with a seven foot tall Rothko painting. Perhaps in the near future art lovers will reclaim that feeling of serendipity using services such as the Google Cultural Institute or by wandering the galleries in virtual reality headsets.

If that optimistic future comes about, it may not matter much where the actual art is. It might even serve as a vindication of consolidated art collections, since big museums are more likely to have the capacity to put the work online. However, in the meantime the public will just have to hope that museums continue their drive to provide more access to stored collections. If they don’t, how will anyone even know all that art exists?

Methodology

The survey data created for this story is available here. Do you want to find out how many of your favorite artist’s works are in storage? We’ve put together a spreadsheet with links to the search pages for dozens of museums. If you find something interesting, email c@qz.com.

- Dozens of museum websites were reviewed to identify those that had complete or mostly complete collection information available online. Larger and more famous museums were checked first. Most of the largest art museums in the world are included, with the notable exception of the Louvre, which does not have complete data online.

- The only criteria for selecting artists was that they be well enough known that it would be reasonable to expect them to appear in several museum collections. (Note: Frida Kahlo is included in the analysis, though her work only ended up being found in two museums that were surveyed.)

- Only one medium was counted for each artist. This excludes from the analysis artist sketches and instances where the artist was working outside the medium they are best known for.

- Prints, lithographs, etchings, drypoints, and other “duplicate” works were excluded from the analysis.

- For the category “oil paintings,” any use of oil paints on any traditional flat surface (canvas, cardboard, etc.) was included. Paintings on objects, tiles, etc, were not included.

- For the category “sculptures,” any three dimensional object that was not obviously intended for created for purpose was included. Jewelry, for example, was left out.

- All counts are based on the data made available online by the surveyed museums. It is possible these museums own works that they have not put online, however, by selecting artists whose fame is not in doubt, the number of these missing works is expected to be small. In addition, museums tend to put works online when they are brought out for exhibition, so any art missing from this analysis is likely to only increase the percentage held in storage.

- Works listed by their owners as being “on loan” were excluded from analysis. It is not known if all museums include this information in their collection index.

- A large installation of 88 Alexander Calder sculptures collectively titled “Calder’s Circus” was excluded from results for the Whitney.

- Data for this survey was collected over a period of several weeks in December 2015 and January 2016. Art may have been moved into or out of storage since this data was collected.

- Every effort was made to be rigorous in the collection of this data. In the event an error is found, please email c@qz.com.

Correction (9:58am ET): The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, is not part of the Smithsonian. A previous version of this story said that it was.