San Francisco glanced at its reflection in a $1.7 million public toilet this week. The comfort station, destined for a plaza in Noe Valley, was put on hold after its price tag became international news.

There was plenty of blame to go around. A construction union said the city was trying to funnel grant money into staff salaries, hence the bathroom’s inflated price; the parks department said the left-wing city council had banned it from doing business with most red-state suppliers, driving up materials costs. Other potential culprits included the uncooperative utility company, the high cost of union labor, and the obligation to review the project under the California Environmental Quality Act. It was a laugh line on Fox News. The sticker shock, at least, was unanimous. $1.7 million? For a toilet, really??

After Heather Knight’s column in the San Francisco Chronicle helped make the public-works project the flush heard ‘round the world, reproached pols canceled the groundbreaking, and California Gov. Gavin Newsom sent the city back to the drawing board.

San Francisco often serves up metaphors for the country’s problems, and it is tempting to use this toilet to spin a grand tragedy about America’s diminished capacity to build, the intractable housing crisis, the disappointment of the state’s high-speed rail project, or the crippling contradictions of American environmentalism. Many of the city’s construction-costs problems are thorny ones, with real trade-offs.

But there is an easy way to produce public architecture that’s more responsive to people’s needs: Spend less time thinking about how it looks. Nearly as eye-popping as the toilet’s price tag was its timeline: The crapper was set to be completed in 2025. A high school freshman participating in community toilet feedback for the thing today would be applying for college by the time he could poop there. And that protracted process, a driver of costs in its own right, owes something to a procedure called Civic Design Review.

For virtually all public projects in San Francisco, winning the design review board’s signoff requires a $10,200 fee and a multiphase approval process. You may be asked to present information on the community outreach process, actual samples of exterior materials, images of applicable references or inspiration for the design, and a “summary of the large idea that is the theoretical basis for the proposed design.”

It’s a comically self-serious request for so basic a piece of public infrastructure. The Golden Gate Bridge received less scrutiny.

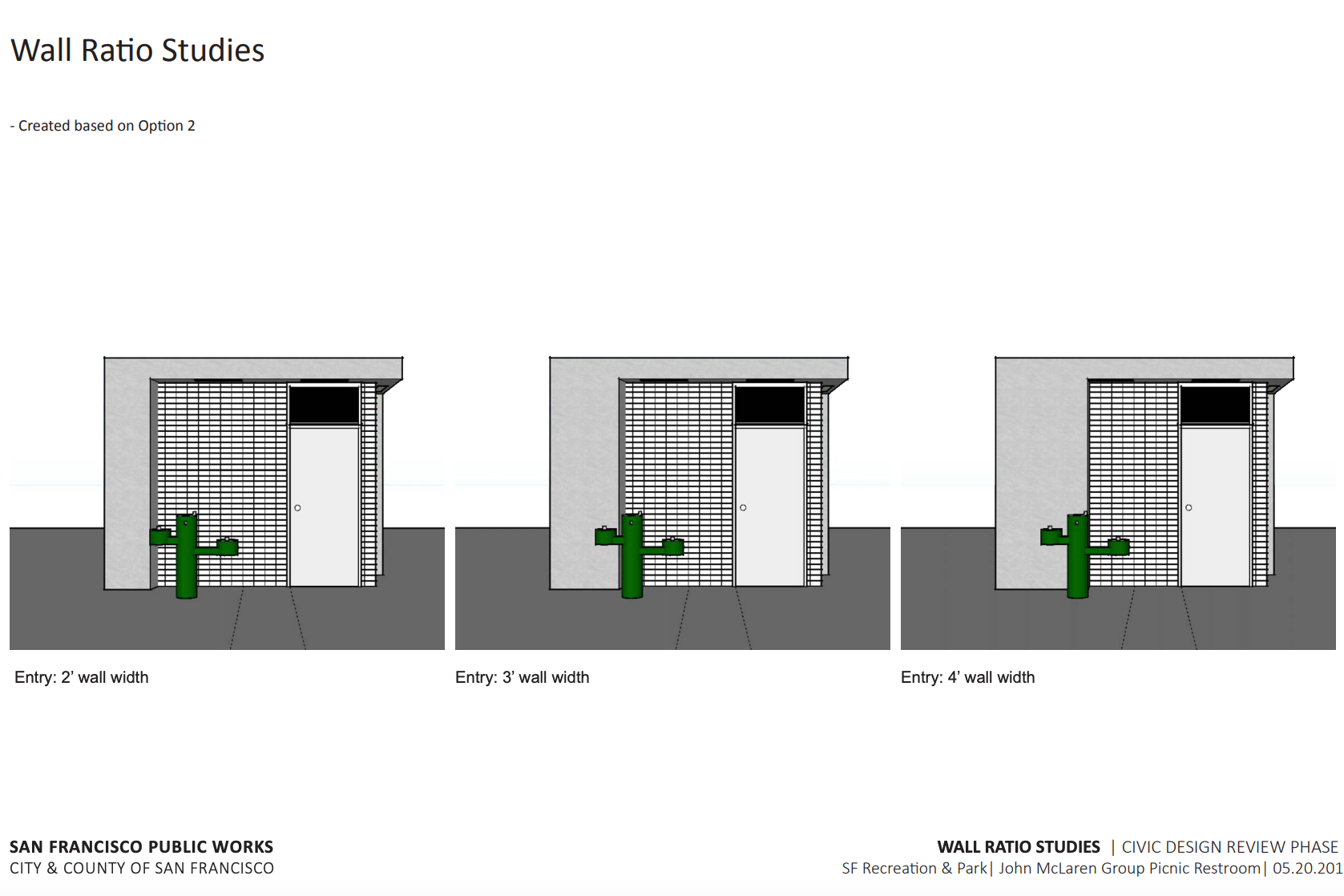

It’s not an outlier, either. I checked in with the design review process for San Francisco’s McLaren Park restroom, which was completed a couple years ago for a no-less-astonishing cost of $1.6 million. It took nine months for that project to move from Phase I to Phase II, at which point the committee of five architects and designers weighed in on issues as minute as the ratio between concrete and tile on the exterior wall. Here’s an example of how granular their input was:

Commissioners chose the pumpkin-colored tile to match the fall foliage. From there, it took another year and a half to open the toilet, which looks … fine.

I was surprised to learn that this civic rigamarole celebrates its 90th birthday this year (though it’s a spry 30 in toilet-construction years). It’s a practice born not of the freeway revolts and the backlash to top-down urban-renewal projects, as close observers of municipal busywork might suspect, but of an older, high-society instinct to beautify the raucous public realm.

In 1932, the Civic Design Review was established as part of the San Francisco Art Commission (now Arts), a voter-approved body to “avoid time-consuming debate, disagreement, conflict, and compromise,” as Susan Rebecca Wels put it in a master’s thesis on the subject. Instead, the commission instantly became embroiled in a “fresco-driven red scare” when Clifford Wight’s painting of a hammer and sickle with the caption, “Workers of the World Unite,” went up in Coit Tower during the West Coast Longshoremen’s Strike. The tower was locked and the mural effaced. Still, the Arts Commission made many noble contributions, including funding the San Francisco Symphony through the Great Depression.

Designing by committee, however, is a more dubious pursuit. Taking years to work on “massing studies” may eventually yield a superior product—but in the case of the Noe Valley Toilet, the long delays imposed by this process are one of the reasons the project isn’t going forward at all. Moreover, in the interim, the public is treated to something very ugly indeed—a Port-o-Potty, or someone peeing on the street. And since people going to the bathroom in public actually is a pretty active political issue over there, this nitpicking feels especially counterproductive.

Despite the controversy this particular story kicked up, San Francisco’s bathroom problem is not such a big deal. But it does stand for a larger, popular philosophy in many big cities—that a committee of interested people, with or without architecture degrees, can coax other designers into producing their best work. The result is smaller and more expensive buildings, slower timelines, and often, the kinds of watered-down designs that please most but thrill few.

Imposing this crit on public agencies, rather than the private developers, makes even less sense, since they are already accountable for their decisions. On balance, I can believe that a civic design commission like San Francisco’s probably does produce superior outcomes for public architecture. But these back-and-forth sessions do not happen in a vacuum. While architects and political appointees trade ideas for toilet design, out there in the real world, costs mount and people need to go. This critique applies to the private sector as well: As Dan Bertolet told me last year about the burdens of Seattle’s design review process, “We have a housing crisis, not an aesthetics crisis.”

Above all, such approaches demonstrate a short-sighted vision of what constitutes an attractive civic realm. Sure, it’s good when the buildings are nice. But if you spend too long getting a building just right, you may impose other aesthetic costs on the city, like an empty lot, or a port-o-potty. What does it mean if you got the mullions just right on a new apartment building if someone is sleeping in a tent by the freight entrance? Of course, that’s to take aesthetic concerns at face value, though aesthetics are not always the real subject of these conversations.

New York City employs a pretty similar approach to San Francisco when it comes to regulating the appearance of the public sphere. But two years ago, the city did something crazy and allowed restaurants to occupy the sidewalk in front of their storefronts with outdoor dining sheds. More than 12,000 of them emerged, arguably the most radical transformation of the streetscape since the arrival of the automobile. It’s chaotic, colorful, and extremely divisive. Some people really hate the things.

I personally think the sheds are a visual plus for the city, by turns elegant and ramshackle, but usually full of people, who are after all New York’s primary attraction. But even if you do not like them—even if you think they, and every bathroom, and every apartment building, deserve multiple doses of architecture school before breaking ground—it would be wrong to compare them to a control experiment in which nothing happens. But for the restaurant shed you’d have a restaurant that went under because it didn’t have outdoor seating to help recover from the pandemic, a dark and forlorn storefront. And by dilly-dallying over the design for a public bathroom, San Francisco has a port-o-potty.